- Groundwork

- Market Engagement

- Groundwork

- Market Engagement

What do I need to be aware of when signing contracts?

This Milestone is about the legal contracts you will use and sign to officially commit to the project and transition it to a fully fledged deal. As business owners, farmers are familiar with contracts and understand the need to carefully review the details before signing any such agreements.

Any nature market deal is likely to involve legal agreements that will be tailored to each set of circumstances. However, for ease this Milestone sets out what contract set-ups are used in this space, common contract types, and other key considerations to ask yourself at this stage.

Disclaimer: The information in this Milestone does not constitute any form of legal advice but instead serves as practical advice that has been written by speaking with lawyers, farmers and other practitioners. We recommend that appropriate legal advice should be taken from a qualified solicitor before taking or refraining from any action relating to your contracts and projects.

Acknowledgements

Sophia Key, Partner and Head of Natural Capital, Birketts

Esther Round, Senior Associate and Biodiversity Net Gain Lead, Birketts

Ross Simpson, Partner, Burges Salmon

David Short, Director / Owner, Lux Nova Partners

Contract Set-Ups

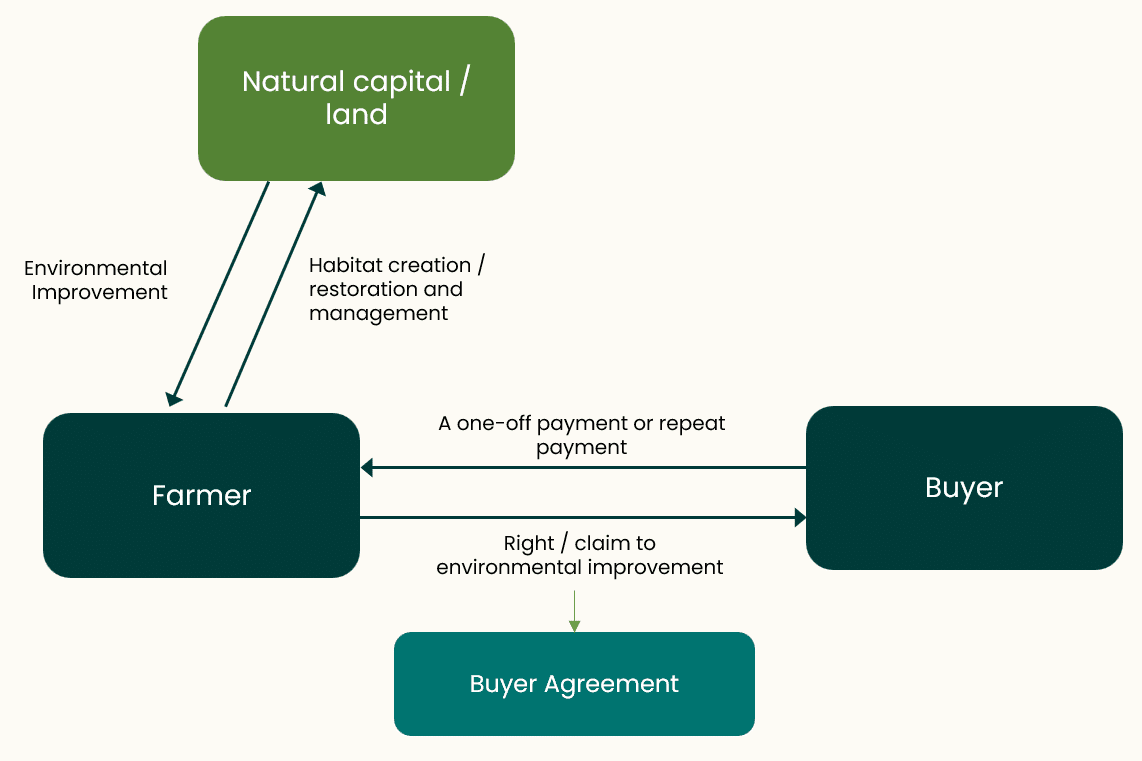

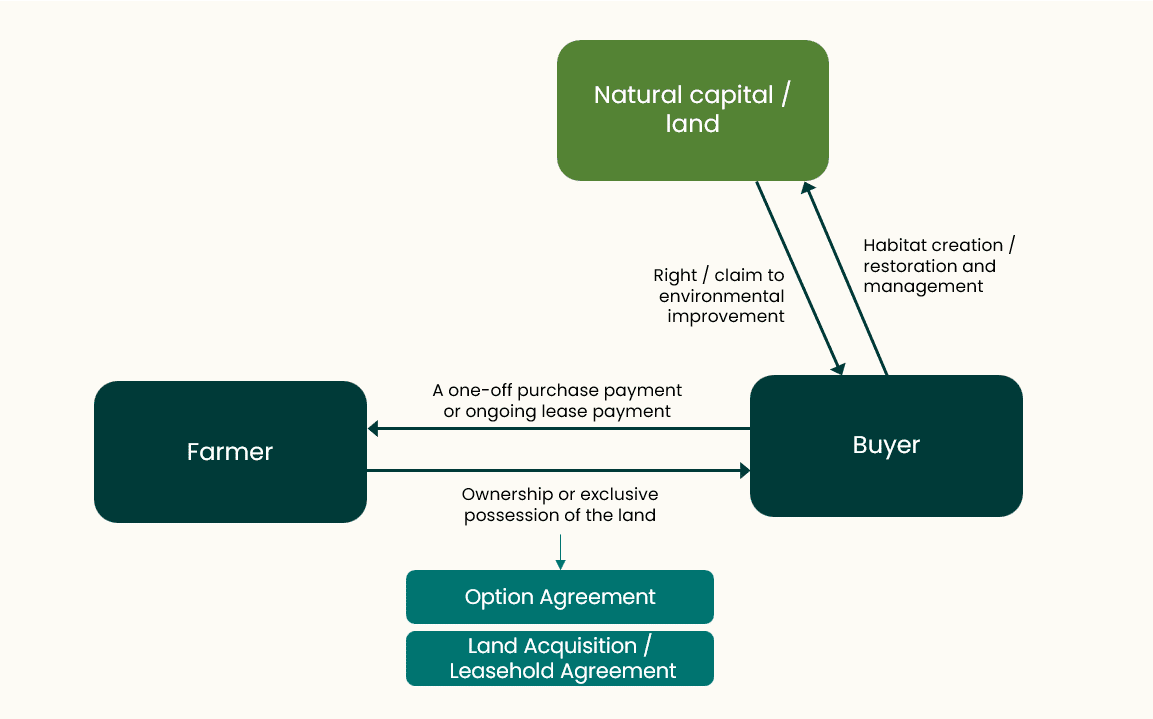

If you’re exploring a nature market deal with a buyer – whether for carbon, biodiversity, water quality or any other environmental outcome – you as a farmer will typically be presented with one of three models, as set out in Birketts’ article: ‘Natural Capital projects: what documents might I have to sign?’.

Each of these models has different contracts with legal and practical implications for farmers. For each model, it is very important that you take accounting, and commercial advice as to the project and how it fits with your business, as well as legal advice on the risk profile. The three models are described below:

The Buyer Delivery Model involves the farmer giving control of the land itself directly to the buyer, either by selling the land or leasing it to them.

Figure 1: Buyer Delivery Model

In practice, this means that the asset the buyer is acquiring is the land itself, but the transaction’s value can reasonably be driven by the value of the environmental improvement that the buyer will create with the land – for example, the market value of the nutrient neutrality credits they create.

In this case, you as a farmer can usually expect to have no involvement with or liability for the management or ongoing monitoring of the land and any habitat creation or enhancement. The buyer (or someone on their behalf) will be responsible for creating/managing the habitat and delivering the environmental improvement the buyer wants.

While this means that the farmer has fewer ongoing responsibilities, risks, and costs than they may have if they were to use other models, they also may get a much lower price for the transaction to reflect this.

In terms of legal documents, farmers can expect to enter into an Option Agreement (or an agreement for lease or conditional contract) with the buyer. The Option Agreement will set out how and when the buyer may exercise their option to buy or lease the land, and may include provisions about certain activities (such as preliminary surveys on the land and other works) prior to buying or taking exclusive possession of it.

During the Option Period where a buyer is reserving the option to buy/lease but hasn’t yet done so, the Agreement might also state that the farmer can’t make significant changes to the land – such as ploughing fields or clearing scrub area, which can affect the nature market potential of the land.

If you sell to them, you will need to sign a Land Acquisition Agreement (and/or a Transfer Deed). If instead you are going to let the land to them, you will enter into a Leasehold Agreement, usually meaning you have no further significant rights over the land for the lifetime of the lease.

Farmers should be aware of a few factors in the Buyer Delivery Model:

- What the buyer intends to do with the land so that it does not impact any of the farmer’s surrounding sites, such as rights of access or use of services that are linked to the land. In some cases, you can build in clauses to the agreement that help with this issue.

- That any such agreement does not adversely affect the farmer’s own commercial obligations or opportunities, for example any existing obligation/opportunity to offset their own carbon emissions.

- If leasing – the farmer should also take advice as to the likely long-term impact on value of their land. At the end of the lease period, the land may have a significantly different market value or certain restrictions on land use. For instance, if a native woodland is planted there, then future governments may heavily restrict their felling, regardless of any previous commercial agreements.

- As mentioned above, farmers should carefully consider what the land will be used for and whether the value of the transaction includes the true value of all natural capital in the land, or whether they should be taking a share in any future value unlocked during the lifetime of the project.

For example, the buyer of the land may not be the entity using the final claim to the environmental improvement itself – such as a corporation using carbon credits to offset their own carbon footprint. Instead, they may be an intermediary – or a third-party project developer – that is looking to sell the rights of claim onwards to a final buyer. This scenario is therefore more akin to the Third Party Delivery Model (see below).

In this case, you may consider a Revenue Sharing Agreement, which means that in addition to payments from the lease or sale of land, you could get a percentage of any future revenues generated from it – such as carbon credits or Biodiversity Net Gain units. However, in the cases of an ongoing Revenue Sharing Agreement, this usually translates to a lower upfront price offered to the farmer, as the Revenue Sharing Agreement offers potential additional compensation.

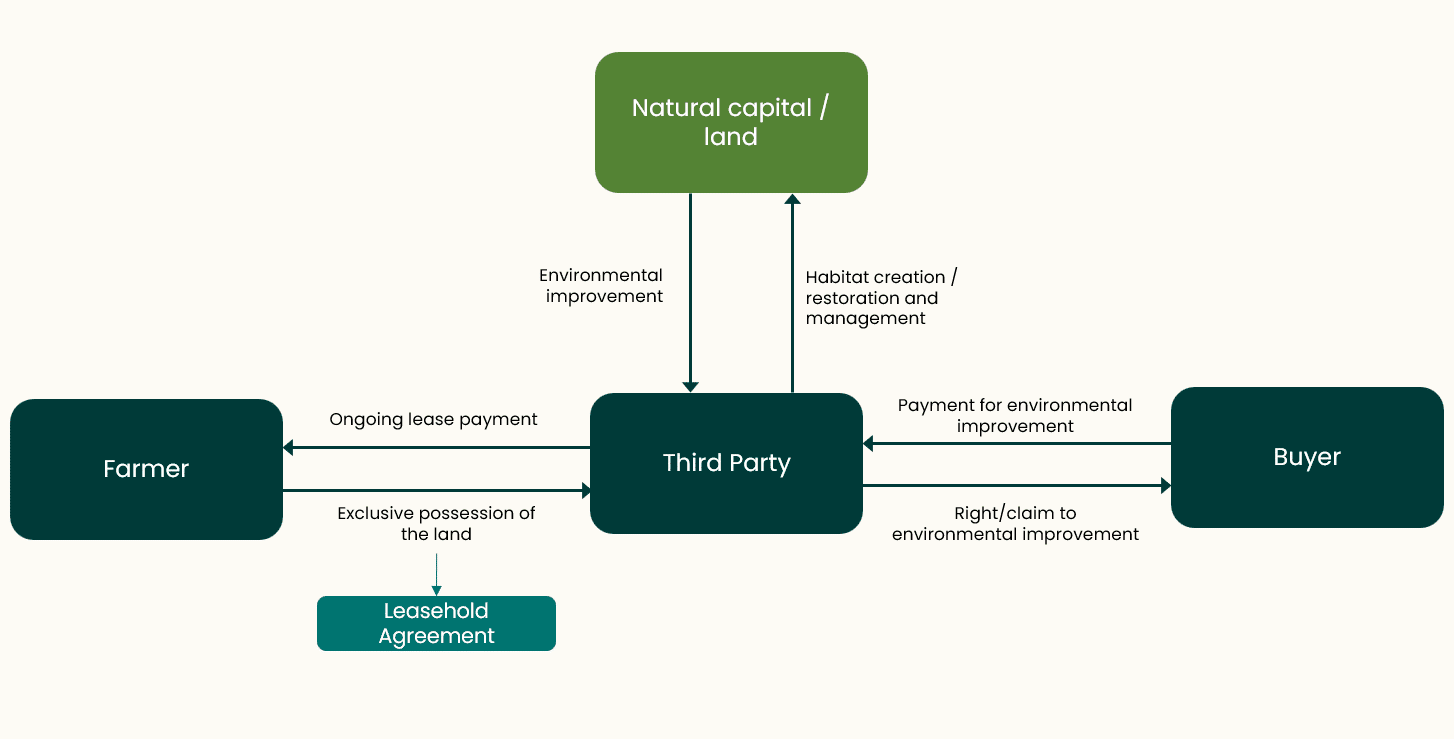

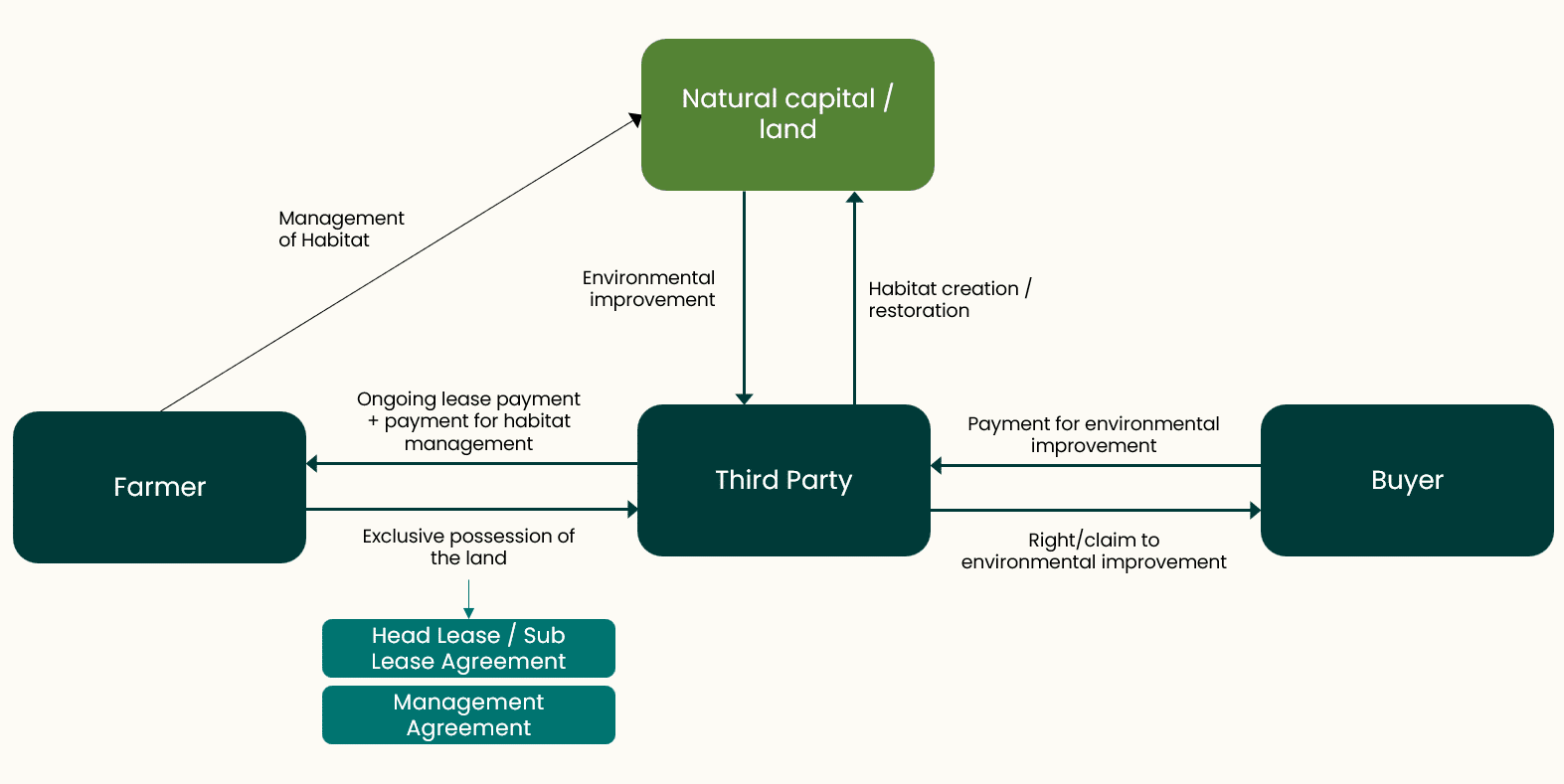

The Third Party Delivery Model is where an organisation separate to both the buyer and farmer takes possession or some degree of control over the land. This third party can be any type of entity, including private companies, environmental NGOs, conservation bodies, or even government organisations.

The third party usually takes a lease of the land using a Leasehold Agreement. In a couple of early cases however, some third parties have offered a Hosting and Maintenance Contract where the farmer retains possession of the land (see this Milestone’s case study on the Wyre Natural Flood Management project for an example of this).

Figure 2a: Third-Party Delivery Model

Like the Buyer Delivery Model, farmers do not pay for the creation/restoration of the habitat (paid for by the third party and recouped from the buyer) and face fewer risks. However, the farmer can expect a lower revenue compared to the value the buyer is paying the third party, as this will be how the third party makes its own profit.

A common example of this model is where habitat bank companies approach farmers with offers to take a 30+ year lease, to create or enhance a habitat for generating Biodiversity Net Gain units.

The exact details of this model can be more varied compared to the Buyer Delivery Model, as responsibilities, risks and rewards can be divided in a range of ways between the third party and the farmer.

For example, farmers can choose to provide some or all the ongoing management of the habitat, in return for an extra payment on top of the lease. In this case, you as the farmer would take a ‘leaseback’ from the third party, involving a Head Lease to the third party and a Sub-Lease back to you, which may offer you better tax benefits.

Where farmers are taking management responsibilities, it’s common for the third party to require the farmer to sign a Management Agreement, which is often called a Habitat Management Agreement in the case of Biodiversity Net Gain. There is often also a more flexible document that is altered as needed by those monitoring the progress of the habitat called a Habitat Management Plan, again found in Biodiversity Net Gain transactions.

In this case, farmers should consider whether they are comfortable committing to manage the habitat over an extended period in accordance with the requirements of the third party, and what their exit options are in case they change their mind. This division of responsibility also needs to be clearly set out in the agreements.

Figure 2b: Third-Party Delivery Model with Leaseback

Note: for certain nature markets (such as Biodiversity Net Gain), it may be necessary for the underlying landowner (the farmer) to sign a planning agreement or conservation covenant such as a s106 with the relevant authority. The agreement / covenant will legally secure the ongoing management of the habitat, but the farmer will not receive any payment under this agreement itself. This process is explained in more detail in the section below.

If the third party were to become insolvent, the farmer may have to continue to meet their obligation under the agreement / covenant without receiving any payment from their (insolvent) third party. Usually, third parties like habitat banks seek to put money into ringfenced accounts to protect against the farmer being exposed to financial loss, if this were to happen.

The Self Delivery Model is where the farmer retains all control of the land and is responsible for creating and managing the habitat, delivering the environmental improvement directly to the buyer.

The contracts used in this model will depend on what is being sold – generically we can call this a Buyer Agreement – but in more specific cases it may be called a variety of different names including for example:

- Biodiversity Unit Purchase Agreement – commonly used for the sale of Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) units

- Offtake Agreement – commonly used for the sale of carbon units (where the buyer commits to purchase carbon units at a specific price in the future).

- Credit Sale Agreement – again, commonly used for the sale of carbon units.

- A fixed payment agreement – commonly used by water companies to pay farmers at regular intervals for management practices that improve water quality.

Note: the Self Delivery Model does not exclude the farmer from using service providers, such as brokers, lawyers, ecologists, or landscape contractors. Indeed, many of these specialists will need to be appointed by the farmer as they are the underlying landholder.

These additional service providers will all have different contracts that may affect the details of the model. For example, there are brokers in nature markets that offer promotion agreements (to promote your units for sale), exclusivity agreements (taking exclusivity on the sale of your units but finding the buyer) and straight brokerage agreements (akin to selling a house).

However, the key is that the farmer is accountable for the delivery and maintenance of the habitat and the environmental improvement – rather than any third party (as in the Third-Party Delivery Model) or the buyer themselves (as in the Buyer Delivery model). Depending on the nature of the project, it may be sensible to set up a separate legal entity to ringfence operations from your wider farm business (see Milestone 6).

As nature markets mature, you may be able to use insurance or indemnity products that help mitigate against the risk of habitat failure. In any case, it’s important for farmers to consider their obligations if pursuing the Self Delivery model.

Across all three of these models, the underlying landowner (either the farmer or the buyer) might be expected to use a covenant or planning agreement that is attached to the land itself. This is to legally protect the habitat on the land to make sure it is used for the required amount of time in such a way to generate the necessary units or mitigation solution.

For example, if the land is sold to a new owner, then they would not be able to destroy or alter the habitat under the defined period of time, as the covenant or planning agreement will continue to affect the land even after a sale.

Depending on what you are selling, different covenants and agreements may be used.

In the case of Biodiversity Net Gain, it is expected that either an S106 agreement will be signed with the Local Planning Authority or the newly designed Conservation Covenants will be signed with the Responsible Body to maintain the habitat over at least 30 years where the project land is in a separate planning area to the development land which will be using the created units. If you as the farmer are the underlying landowner, this is in addition to any agreement you have with the buyer or third party, and is designed to give an extra layer of protection to the habitat.

Other covenants can be used with specialist bodies, such as a Forestry Dedication Covenant with the Forestry Commission, which likewise obliges the landowner to manage a new woodland in a particular way for a defined term.

Common types of contracts

There are many different types of contracts that can be used for a nature market deal. These can each be tailored with clauses and other features to the circumstances of the deal, and it is important to review these carefully with legal advice.

The table below describes the most common contracts that you might encounter.

Note: this is not an exhaustive list of contract types but has been written from speaking to lawyers, farmers, and other stakeholders in nature markets. If you know of any contract types that you feel should be listed, please contact us at [email protected].

| Contract Type | Summary |

| Option Agreement – for Land Acquisition or Leasing | An Option Agreement is a contract between the owner of a property and a potential buyer/leaseholder. The Option Agreement gives the potential buyer/leaseholder the right to buy or lease the property either at an agreed price or at its market value.

In nature markets, project developers typically use Option Agreements when they intend to purchase or lease land to develop a habitat. The Option Agreement will set out how and when a buyer/leaseholder may exercise this option, and may include provisions about certain activities which they may carry out (such as preliminary surveys on the land and other works) prior to buying or taking exclusive possession of it.

The period of time where the potential buyer/leaseholder has this option is called the Option Period, and the farmer may face restrictions around the land use (such as no actions to significantly alter the habitat) during the Option Period.

|

| Land Acquisition / Sale Agreement and Transfer Deed

|

An agreement to purchase the freehold of the land in its entirety, whether for the purchaser’s own use or as an investment and is the contract which binds the seller and the buyer to sell and buy the land on a specified date.

The Transfer Deed is the legally binding document which will transfer the legal title in the land to the Buyer in consideration for the agreed payment.

|

| Lease Agreement | Sometimes called a land lease or a ground lease. The lease is granted for a finite period of time and gives the tenant exclusive possession of the land.

This period of time can be fixed and then may be extended. Leases are given with the intention for the tenant to create an ‘estate in land’ – an interest in the land, that can be transferred, sold, charged or licensed, such as productive farmland or new buildings. In nature markets, land can be let to a third party to deliver an environmental project such as a new woodland, a nutrient mitigation wetland or a species rich grassland.

|

| Leaseback

(Head Lease and Sub Lease) |

Land can be leased from the farmer to the buyer / third party through a Lease Agreement. In the case of a leaseback, this first lease is called the Head Lease.

If both parties are amenable, the third party / buyer can then lease back the land to the farmer on a Sub-Lease, usually for the farmer to maintain the habitat that the third party / buyer has created or enhanced, in consideration for an extra fee in addition to the payment due under the Head Lease.

As this type of arrangement keeps the farmer as an active manager of the land, it can have beneficial tax implications. It is advisable to explore these with your land agent or accountant.

|

| Contract Type | Summary |

| Habitat Management Agreement

|

A Habitat Management Agreement is a services agreement between two parties – someone taking legal responsibility for managing a habitat (such as a farmer or a third party that has leased land) and someone that has interest in the habitat’s condition (a buyer, or in the case of a leaseback model a third-party project developer).

In nature markets, a Habitat Management Agreement is usually signed alongside a sales agreement for ecosystem services, namely for carbon credits and Biodiversity Net Gain units.

In the case of Biodiversity Net Gain, this is often accompanied by a Habitat Management and Monitoring Plan (see below), which is a more flexible document that can change depending on ecologists’ instructions.

A Habitat Management Agreement will likely reference the Habitat Management and Monitoring Plan so that it can capture this flexibility without changing the legal agreement itself.

|

| Habitat Management and Monitoring Plan | A Habitat Management and Monitoring Plans is self-descriptive and sets out the management and monitoring practices for a habitat.

It is required in Biodiversity Net Gain projects, though its general purpose can be applied to other nature restoration projects.

You will need a Habitat Management and Monitoring Plan to register Biodiversity Net Gain units on the Biodiversity Gain Site Register, which is a prerequisite to creating biodiversity units that can be sold onwards.

The Habitat Management and Monitoring Plan ensures that not only will the habitat be managed appropriately, but also that suitably frequent monitoring takes place during the lifetime of the agreement (with BNG a minimum 30 years) by qualified personnel.

Note: a Habitat Management and Monitoring Plan is not in fact a contract or legal agreement. However, it may get appended to contracts or referred to in relevant contracts, such as Biodiversity Unit sales agreements. It has been included in this table as it is often confused with a Habitat Management Agreement.

|

| Hosting and Maintenance Contract | A contract between a project delivery vehicle and landowners or land managers, whereby the latter agree to host and maintain certain nature-based interventions (such as NFM interventions) on their land in return for a periodic revenue payment e.g., an annual fee. This is a commercial contract, not a lease agreement and there are no land rights accruing. The services provided under this contract would typically attract VAT.

Note: this contract was developed and pioneered by the Wyre Catchment Natural Flood Management project in 2023. It is currently being explored for other uses by the project developer (the Rivers Trust).

|

| Licence Agreement | A licence gives permission for the licence holder to do something specific on the land and occupy it alongside someone with possession of the land, such as the owner or tenant.

It does not grant exclusive possession, as with Leasehold Agreements. For example, grazing licences are created for the purpose of grazing horses, cows or other animals. They are not usually longer than 12 months. However, if care is not taken, these can sometimes be legally interpreted as Farm Business Tenancies – for instance, if exclusive possession is given in practice.

In nature markets, licence agreements can sometimes be used on habitats that deliver sellable environmental improvements. For example, species rich grassland that delivers Biodiversity Net Gain units can also host non-intensive livestock grazing, which can be licenced to another farmer.

|

| Contract Type | Summary |

| Conservation Covenant | A conservation covenant agreement is a private, voluntary agreement to conserve the natural or heritage features of the land.

A conservation covenant is an agreement between a landowner and a Responsible Body, which specific to each local planning area in England. As of November 2023, no Responsible Bodies have been designated. They are likely to be Local Authorities, other public bodies, conservation charities and conservation organisations.

The conservation covenant sets out obligations in respect of the land that will be legally binding, not only on the landowner but on subsequent owners of the land. A conservation covenant can impose both positive and negative obligations. This might be, for example, an agreement to maintain woodland and allow public access to it, or to refrain from using certain pesticides on native vegetation.

To enter into a conservation covenant you must either be the landowner or, if a tenant, have at least 7 years remaining on your tenancy. In the context of nature markets, conservation covenants would ensure that created habitats are maintained by legally binding the land manager and future owners of the land to maintaining the newly established or maintained habitat.

One use will be in the context of Biodiversity Net Gain in the planning system, which will become mandatory from January 2023. In order to register offsite units on the Biodiversity Gain Site Register you will need to show that you have bound your land using either a planning obligation (most likely a Section 106 Agreement or a conservation covenant.

They are expected to be used in Biodiversity Net Gain unit sales, once this becomes mandatory for most new developments in England (currently expected to be from January 2024).

This type of legal agreement was introduced in 2021 by the Environment Act (2021).

|

| Section 106 Agreement

|

Section 106 Agreements are legal contracts between Local Planning Authorities and the underlying landowner on which a habitat is being created or restored. This type of agreement has been used for several years now.

Section 106 Agreements are often (but not always) linked to planning permissions for new property developments and can also be known as planning obligations. In the context of nature markets, they are drafted when it is considered that a property development will have significant impacts on the local environment that cannot be mitigated by the property design itself.

This obligation can often be met through payments, usually paid in instalments at key stages during the construction and/or occupation of a development. These are known as trigger points.

|

| Section 33 Agreement

|

Section 33 agreements are legal contracts between Local Planning Authorities and the underlying landowner on which a habitat is being created or restored which are akin, in terms of obligations and responsibilities on the landowner, to a section 106 Agreement.

|

| Contract Type | Summary |

| Biodiversity Unit Purchase Agreement | These are agreements between those landowners / third parties delivering BNG units themselves and those parties who wish to buy the units which document the consideration being paid for those units. They do not create any interest in the land itself and are sales agreements for the units only.

|

| Option Agreement | An option agreement for purchasing credits and units means the buyer has an ‘option’ to buy credits and units for a period of time. The terms of the sale are agreed in the option agreement and the buyer pays a ‘deposit’ or ‘reserve fee’ on signing the option (e.g. 10%). Importantly, the buyer can choose to exercise their right to buy or not.

It is anticipated that option agreements will be used often for Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) agreements, as at the point of applying for planning permission the buyer (e.g. a property developer) may need to show to the planning authority that it has access to the relevant number of offsite biodiversity units. The option agreement enables the property developer to show it has access to the units, without needing to buy them before securing planning permission.

Note: In principle, an option agreement can be used for the sale of anything – commonly this is used for property acquisitions (see above).

|

| Offtake Agreement / Credit Sale Agreement | An offtake agreement or credit sale agreement is a legal contract in which a buyer agrees to purchase a set amount of units or credits (commonly carbon credits) at set prices and defined points in the future – sometimes several years in the future.

Long-term offtake agreements can be arranged prior to the habitat being created or restored and can help the seller of these credits (either the farmer or a third party) to secure repayable finance to meet these up-front costs.

It is akin to a power purchase agreement (PPA), which is used in renewable energy projects around the world.

|

| Nutrient Neutrality Unit Purchase Agreement | These are agreements between landowners and the buyers of nutrient neutrality units that document the sale of the units in consideration for a payment.

|

| Contract Type | Summary |

| Contract Delivery and Management Agreement | A commercial contract between the person or entity responsible for delivering the habitat (such as the farmer, buyer or a third party), and a separate contractor, whereby the latter commits to deliver environmental interventions on the land.

In some cases, the contractor can remain responsible for the habitat’s continued maintenance through management of relationships with landowners. Examples of these interventions include peat restoration, tree planting, delivery of natural flood management interventions or river restoration.

The main contractor might be an environmental NGO or a private sector civil engineering firm, for instance.

|

| Revenue Sharing Agreement | A Revenue Sharing Agreement is where a percentage of future revenues from a transaction are promised to a party outside of that transaction. For example, a farmer that leases land to a habitat bank company for the purpose of BNG units could negotiate a Revenue Sharing Agreement, so that they receive a percentage share of any sales of BNG units on top of the lease payments for the land itself.

Note: negotiating this type of agreement can mean that the third party offers a lower (guaranteed) lease payment, as the farmer has the chance to financially benefit from the agreement if revenue is made later on.

|

| Promotion Agreement

|

A commercial contract between a landowner and a promoter where a promoter will carry out certain processes to promote the sale of the natural capital opportunities and units on the land. The promoter will ordinarily receive a percentage of any revenue sales as their fee for being included in this process.

|

| Exclusivity Agreement

|

An exclusivity agreement is an agreement that gives an exclusivity for two parties (e.g., a farmer and a corporate) to buy or sell units or land and will prohibit the parties from doing deals with any other third parties during the pre-agreed exclusivity period.

|

| Brokerage Agreement

|

A commercial contract between a landowner and a broker where a broker will actively market the sale of the natural capital opportunities and units on the land – this would be akin to an agent selling a house. The broker will ordinarily receive a percentage of any revenue from sales as their fee for being included in this process.

Note: some nature market brokers may also provide services to support the farmer in developing and delivering an environmental project, for example by providing or procuring ecological services, or by helping to secure additional grant funding. In this sense, the broker can take on a role more akin to a third-party project developer.

|

Other Key Considerations

The above two sections give an overview of the types of contracts that you, as a farmer, might encounter. However, anecdotally there are other, more practical questions that farmers ask themselves when they reach the contracts stage.

Based on speaking with farmers, lawyers and other practitioners, these are listed below for your consideration. This is not an exhaustive list of considerations, but we hope this will be useful to farmers who are navigating the development and signing of their contracts.

Within this Toolkit, we have left this Milestone until last because we think it’s wise to design and clarify as much of the project as possible before working on the contracts in more depth. While farmers can seek legal guidance on the project early on and get an idea of the types of contracts, developing the actual contracts can take much more time and resource. Legal costs can run up when key elements of the project are not agreed or are continually revised.

You might consider using Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with all counterparties (buyers, ecologists, brokers, other farmers etc.) to get as much detail as possible set out before engaging with lawyers. These are non-binding agreements that can help ensure everyone is on the same page.

There are free templates available on the internet that can be adapted to fit your project. One project (the Wyre River Natural Flood Management project) has also offered its MoU template for others to use.

Through this approach, lawyers can be brought in later in the process to convert the MoUs into legal contracts. This approach is not failsafe, and legal advisers may identify important issues that have not been covered in an MoU. However, as a general rule this is a form of best practice when it comes to developing legal contacts.

Feedback from farmers and lawyers alike has shown that a major delay or even an insurmountable barrier when developing contracts can occur once stakeholders consider the downside scenarios that might take place, and what they are liable for should these happen.

In your deal or transaction, people will presumably be happy if everything goes according to plan, but when contracts are getting drawn up, there are often discussions about clauses that set out what will happen if things go awry. This can result in a sobering moment for people that are liable to deliver certain things.

For example, what if:

- The habitat restoration / creation works are delayed by a year?

- The habitat is partially or completely destroyed?

- The buyer or the farmer becomes insolvent?

- There is a change in the underpinning legislature, regulation or Standard?

- The farmer wants to sell the land in the future?

If stakeholders don’t consider these scenarios and ask themselves what they’re comfortable with before contracts start getting drawn up, there’s a chance that they might withdraw from the agreement entirely.

It’s therefore always advisable to discuss these downside scenarios with all stakeholders in the transaction early on, to save time and potential costs (like legal fees) in case the transaction isn’t viable.

Lawyers will send out virtual copies of the fully signed contracts to the relevant counterparties, including what some call a ‘contract bible’ pack of all contracts to the project team. In case there is a need to review these later, it is important to save these down in an accessible way to the project team and other key stakeholders, while preserving any confidentiality that the contracts require.

This access may come in handy when it comes to various critical moments of the project’s implementation phase, or if amendments to contracts are requested after signing and a separate law firm is engaged for this work.

You’ll note that these downside scenarios are discussed in Milestone 6 (Liability & Risk Management), as well as the recommendation to make sure legal agreements reflect everyone’s understanding and risk appetite.

The best choice of legal advisor will often come down to two criteria; do they have the expertise for your project, and are their fees in line with your budget? It is also worth noting that some buyers of natural capital services will offer to pay your legal and accountancy fees, especially if they have approached you with the opportunity.

As to expertise, nature markets and natural capital is a relatively new area that legal firms, along with most other stakeholders in this space, are building their expertise in.

As a starting point, a simple internet search of ‘natural capital lawyers’ can give you a list of names to consider. You can then combine their speciality with other factors that are important to you, such as experience representing farmers and dealing with rural property matters.

The best firms to approach can also depend on what contracts you are seeking. For example, if your project does not involve land acquisition or leasing, you may not require a lawyer with a focus on Commercial Property or Land law.

If you are still unsure on who to approach, it is worth speaking with other farmers across the country that have explored their nature market opportunities and what legal advisor they’ve used. You can search for the farmers featured in the case studies of this Milestone as a starting point.

You can also speak with your project stakeholders – e.g. your buyers and delivery partners – as to which law firm they recommend engaging with. However, it is important to note that each of these parties will most likely have their own lawyer at this stage, and thought should be given as to whether everyone would be more comfortable having separate legal representation.

As to budget, a common best practice is to approach three or four law firms and obtain quotes for the work, in order to make a more informed choice. Bear in mind that pricing structures may vary (see below).

Legal services are usually provided through a formal letter of engagement that sets out the agreed scope of services and the fee structure.

Legal firms are often prepared to charge for their work in different ways, including:

- Time based fees – whereby they will provide a list of hourly or daily charge out rates of different staff members in the engagement letter and you will be charged based on time spent on the project by different staff. This type of engagement can make it difficult to manage costs as the more complex the project, the more time your legal advisers may spend on it and the more you get charged.

- Fixed fees – whereby the firm commits to either an overall fixed fee for the work or fixed fees for certain elements of work, such as specific contracts. This approach means it is easier to control costs, but the law firm may set conditions around this such as up to three versions of a certain contract, or a time limited quote that assumes the transaction is completed by a certain date.

A legal firm might offer pro bono or low-bono (discounted) services for several reasons, including:

- exposure to a new sector,

- staff training, or

- as part of a CSR strategy – such as delivering environmental or social impact.

A legal firm’s decision to offer pro-bono or low-bono services generally will have been decided internally beforehand. You should not attempt to convince a law firm that does not offer these services to offer low/pro bono to your project.

If it does offer these services and you think your project delivers on the legal firm’s criteria, then naturally it’s worth pitching your project and asking!

Ideally, your appointed legal firm would be provided with signed non-binding agreements, such as Heads of Terms, Memorandums of Understanding, Letters of Intent and term sheets between you and any counterparty.

As a general rule, the more information you can provide to your lawyers up front, the better. You can even share the business plan (if you’ve created one) to give them a fuller view of the project.

It is not advisable to sign any binding documents until you have had the chance to take accounting, commercial and legal advice on these.

If you are building a nature market transaction or deal with other farmers, such as your neighbours, then the nature of your partnership and the ecosystem service being sold may involve multiple different contracts. For example, with Biodiversity Net Gain there are always direct contracts with each of the landholders. This might differ you are selling nutrient reduction solutions to a local water company through a legal entity that you’ve formed as a seller collective.

If there are multiple contracts with each farmer, and you feel comfortable that your interests are aligned, then you may consider joint representation and a common contract ‘template’ with identical clauses and fair terms. As well as transparency, this would also save on legal costs.

As an example of where this approach was taken, the Wyre Natural Flood Management project involved a ‘seller group’ of farmers and estate owners. Each seller signed the same contract (with different price terms and ecological interventions for their lands), and the contract template was reviewed by the in-house estate manager of one of the sellers, to make sure that each amendment was fair for all farmers. You can read more about this process here.

At the moment, there is a lot of uncertainty within nature markets, but it is clear that change is going to happen. Things like further government legislation, changes to tax treatments, and frameworks to regulate the way Standards and Codes work, are sure to happen in the years to come. You can read more about this in the Public Sector Funding & Policy section.

Depending on your project’s design, you may have several contracts to sign that each commit you (and the other stakeholders) to certain actions, which can leave people feeling ‘on the hook’ until all contracts are signed.

For example, as the seller you might not feel comfortable committing to delivering carbon benefits to a buyer, until you have signed a contract with any ecological contractor to help restore or create your habitat for a fixed cost that you’ve built into your cashflow forecast.

You may also be asked to sign a Conservation Covenant or another planning agreement that places restrictions on your land use. However, this agreement itself doesn’t include the payment for the ecosystem service – which would be covered in another contract with the buyer or third party. Naturally, you would want to make sure that your income stream is secured before you tie up your land.

To remove this tension, your lawyer can play a key administrative role in the completion phase. One law firm will often be responsible for collecting all signatures from counterparties, which is now almost always done electronically with software such as DocuSign or Dropbox Sign. If there are several contracts that are inter-linked, lawyers can retain or ‘hold’ contracts signed by counterparties, so that no one contract is being signed without the rest in tandem.

Almost all the legal documents a landholder will be asked to sign will have an end date. This might be 30 or 40 years into the future. When taking legal advice, the farmer should be clear on the period of time they will be subject to the legal documentation for.

At the end of the period of time, the landowner will take free from the covenants contained within those documents, but you should be mindful that changing the use of the land at the end of that period of time will be subject to the rules, regulations and planning considerations of that time.