Project Summary

The Wendling Beck Project (WBP) is a collaboration between four Norfolk landowners that are re-purposing almost 2,000 acres of arable land to create a landscape-scale nature recovery project. It has been supported since 2020 by environmental NGOs, local authorities, central government pilots, and a water company as an exemplar for leveraging nature finance to drive land-use change.

WBP is demonstrating how new compliance markets, such as biodiversity net gain (BNG) and nutrient neutrality (NN), can deliver high-integrity outcomes for nature alongside co-benefits such as natural flood management (NFM), climate mitigation, and social impact, whilst also balancing food production.

It is providing in excess of 3,000 biodiversity units, across 35 different habitat types to developers and enough nutrient credits to unlock ~2,000 homes in Norfolk. Through these and other revenue streams, employment across the Project is predicted to increase by 1,000% from the previous farming businesses.

Quick Stats

- Location: Norfolk

- Size of Land: ~2,000 acres

- Landholding sizes: 250 – 650 acres

- Tenancy & Ownership: Owner-occupiers

- Nature Market Focus: Biodiversity Net Gain, Nutrient Neutrality

- Project partners: The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Anglian Water, Norfolk County Council, Breckland Council, Natural England, Norfolk Wildlife Trust, Norfolk Rivers Trust, Norfolk FWAG

Acknowledgements

With many thanks to the following individuals for their time and insight:

Glenn Anderson, Strategy Lead and Co-Founder, the Wendling Beck Project

Rob Cunningham, Europe Resilient Watershed Programme Director, The Nature Conservancy

Date Published: 04/07/2025

Key points

- The landowners had no previous experience collaborating on environmental projects, but shared a high level of trust and agreed that their land was becoming less financially and environmentally resilient under traditional farming practices.

- They note that forming the initial WBP concept required much time and contemplation, and that the COVID-19 lockdowns offered space for deeper conversations.

- WBP partnered with key NGOs, such as the neighbouring Wildlife Trust and the Nature Conservancy, to bring in key skills and increase the Project’s scope.

- A Limited Liability Partnership and a “What-If Agreement” were formed to formalise commitments and address scenarios like succession planning and land sales.

- Landowner compensation includes annual land commitment fees, reimbursement for time and costs, and “Land Years” that distribute any WBP profits.

Origins of the landowners’ collaboration

The WBP was founded in 2020 by four neighbouring farmers and landowners who, though on friendly basis, had never worked together on environmental projects.

Over the years, all four landowners have witnessed increasing environmental and financial pressures on their farm businesses (see Milestone 1). In parallel to these risks, they began to talk about the potential opportunities – such as the upcoming Environment Act (2021) and its introduction of Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG).

Conversations intensified significantly over the COVID-19 lockdowns, as the group had more time to step back from their daily operations and reflect on future business challenges. The landowners found that they all shared interest in conservation, and researched ways to reverse the decline of nature on their land. Glenn Anderson, Strategy Lead and one of the founding members of WBP, says that the group drew inspiration from reports like Making Space for Nature (2010) and Green and Prosperous Land (2019), which highlight landscape-scale decision making.

Seeking external partnerships

To broaden the Project and bring in expertise, the landowners approached Norfolk Wildlife Trust (NWT) and Norfolk County Council (NCC), which had plots of land neighbouring their farms. The landowners invited these organisations on several site visits to discuss the potential of incorporating their land in the masterplan. Before committing to a formal partnership – underpinned by a Memorandum of Understanding – the landowners spoke to the NWT and NCC on a weekly to monthly basis (depending on time constraints) to ensure their goals could be fully aligned to the WBP.

The landowners met on an ad-hoc basis until 2021, when they approached The Nature Conservancy (TNC), an environmental NGO that had been recommended by a contact at the Norfolk Rivers Trust. The landowners gave a virtual pitch of its aims, including an environmental masterplan that would be collectively designed, managed and executed by the landowners and its partners (see Milestone 1) and asked for initial funding and support to develop the Project. TNC agreed to this due to its interest in nature markets, but also due to the extent of collaboration demonstrated.

TNC encouraged the WBP to apply for feasibility funding through the Natural Environment Investment Readiness Fund. TNC also provided pro-bono project management support to help write the NEIRF bid, which was ultimately successful (see Milestone 1).

“Things really shifted gears when we got TNC’s support. We went from ad-hoc discussions to weekly calls and a tight project management structure. With their support and guidance, we developed basic but essential things like core delivery objectives, a stakeholder plan and a communications strategy.” TNC also connected the group with specialists and advisors to come in and develop the masterplan and other parts of the project – such as its biodiversity baselining (see Milestone 3).

Formalising collaboration

Anderson notes that, while all landowners were engaged and supportive of the concept, levels of capacity varied over time, and roles evolved naturally. For example, Rosie Begg is one of the landowners that initially led the research on regenerative farming methods, and is now the Regenerative Farming Lead. High mutual trust between the landowners supported this flexibility.

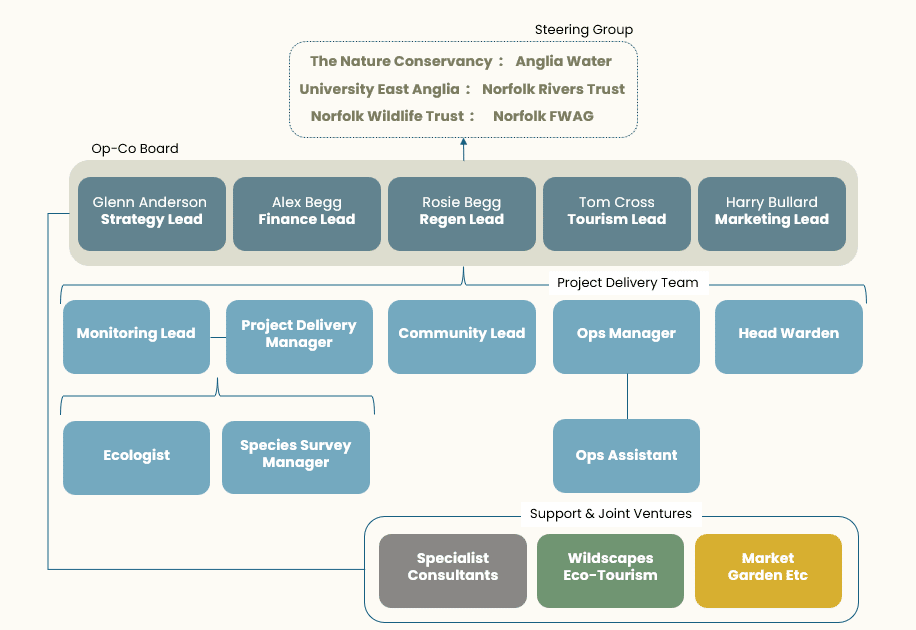

As of July 2025, the team structure includes the landowners as the Op-Co Board and allocates specific roles within the Project. The supportive project partners act as a Steering Group, and eight further employees support the Project’s delivery.

Figure 1: Wendling Beck Project Team Structure

To formalise their commitment, the landowners formed an operating company (OpCo) through a Limited Liability Partnership (LLP – see Milestone 6). The OpCo is supported by an underlying Agreement (LLPA) – which is known by the landowners as the ‘What-If Agreement’.

Signed in October 2024, the LLPA sets out how the OpCo is run, including meeting cadence and decision-making processes, considerations around landowner succession, and how landowner compensation is calculated (see below).

The LLPA also references several potential scenarios that required careful deliberation – such as succession planning. For example, all land ownership is retained by the original landowners but the LLPA sets out the agreed process for when a landowner may wish to sell land included in the environmental masterplan. This includes how the OpCo has the Right of First Offer to buy and retain the land. The agreement also sets out the process for if there is a ‘deadlock’ disagreement between the four landowners.

Originally intended as a short framework, the LLPA took two years to develop and reached 57 pages, as legal discussions raised additional risk considerations amongst the landowners.

Anderson says “while all these conversations were happening, we were still eager to get going and not let the bureaucracy hold us back too much…In the beginning we would get hung up on the small details, like whose tractor would be used for what field work, but as things progressed we learnt to prioritise pragmatism, be comfortable with uncertainty and remain flexible.”

In 2022, the WBP landowners started to formally record their working hours towards the Project. However, Anderson says not all of these hours will be claimed, as they are regarded as pre-revenue project development costs, and that the landowners are comfortable taking a longer-term outlook on compensation.

Deciding compensation

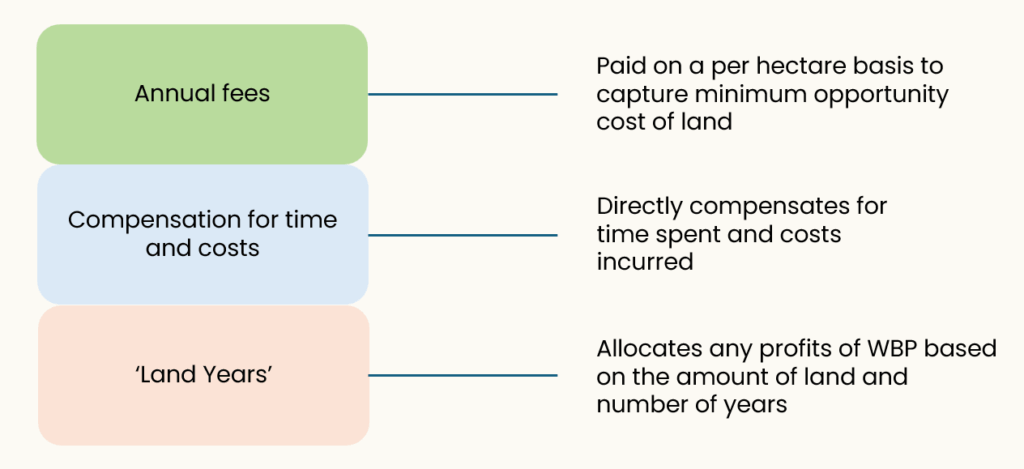

The landowners and WBP’s project partners agreed that profits should be managed centrally to ensure the Project’s longevity (see Milestone 5), but also recognised the need for a system to decide on landowner compensation, which is made up of three components:

Figure 2: Wendling Beck Project Landowner Compensation

- Annual fees for land commitment

A basic annual fee is paid to the landowners that captures the minimum opportunity cost of putting their land into the environmental masterplan. This is calculated using the regional Farm Business Survey, which provides data for opportunity cost calculations, and is inputted into the WBP financial model. The fees are based on hectarage and are reviewed annually in line with any new survey data.

- Direct compensation for time and costs incurred

Direct costs incurred and time spent on the WBP by the landowners themselves – such as habitat creation and maintenance – are paid out directly to the landowners, with fees determined by NAAC contracting prices. Any activities not covered by these rates, such as desk-based work, is recorded on a time sheet and paid out each month at a pre-agreed rate (£/day).

- ‘Land Year’ payments for any profits distributed

While the landowners agree to manage the WBP’s funds centrally and in perpetuity (see Milestone 5), it was also agreed that a system of profit allocation would be needed, should any profits be distributed.

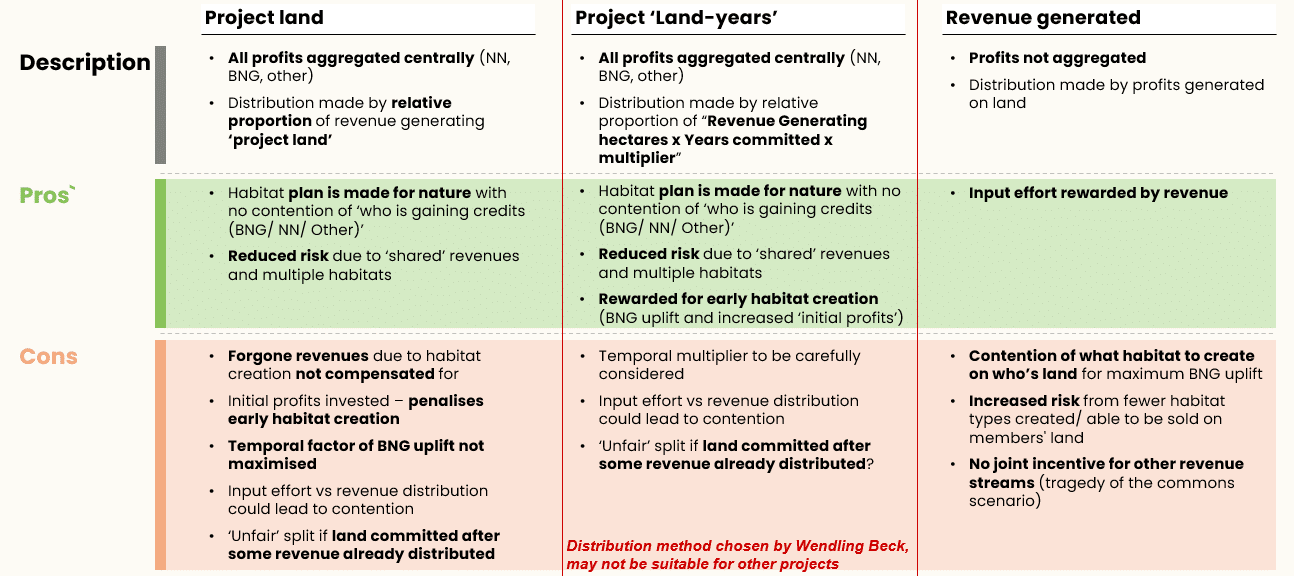

The landowners and project partners – including TNC – debated several different options, such as allocating profit on the basis of how much land each landowner has committed, or letting landowners keep a larger portion of the revenues generated directly from their sites. Key considerations for how profits should be allocated and distributed included:

- Amount of project land contributed by each landowner.

- Different levels of forgone arable revenues due to habitat creation.

- How long the land has been committed – including the ‘temporal multiplier’ of BNG and its effect on the number of biodiversity units available as more time passes.

- The habitat plan for nature uplift versus the commercial viability of some habitats and sites over others – such as the ability to sell biodiversity units and nutrient credits.

- The potential for other revenue streams and their effort required – such as eco-tourism management.

Ultimately, WBP decided on a concept called ‘land-years’, which will allocate any distributed profits to landowners based on:

The number of hectares they’ve committed (x) the number of years committed (x) a multiplier that can be based on particular circumstances for that landowner.

Examples of what might set the multiplier include higher arable revenues forgone, or land that fails to generate a direct return but is key to the project, such as SSSI land. This multiplier is agreed between the landowners.

A table summarising the pros and cons of the profit distribution methods considered can be found below:

Figure 3: Distribution Methods Considered

Anderson emphasises that, while this approach may not appeal to all projects with multiple landowners, the concept of land-years allows the landowners of the WBP to take a longer-term view that recognises the collective efforts of the group.