Project Summary

The Wendling Beck Project (WBP) is a collaboration between four Norfolk landowners that are re-purposing almost 2,000 acres of arable land to create a landscape-scale nature recovery project. It has been supported since 2020 by environmental NGOs, local authorities, central government, and a water company as an exemplar for leveraging nature finance to drive land-use change.

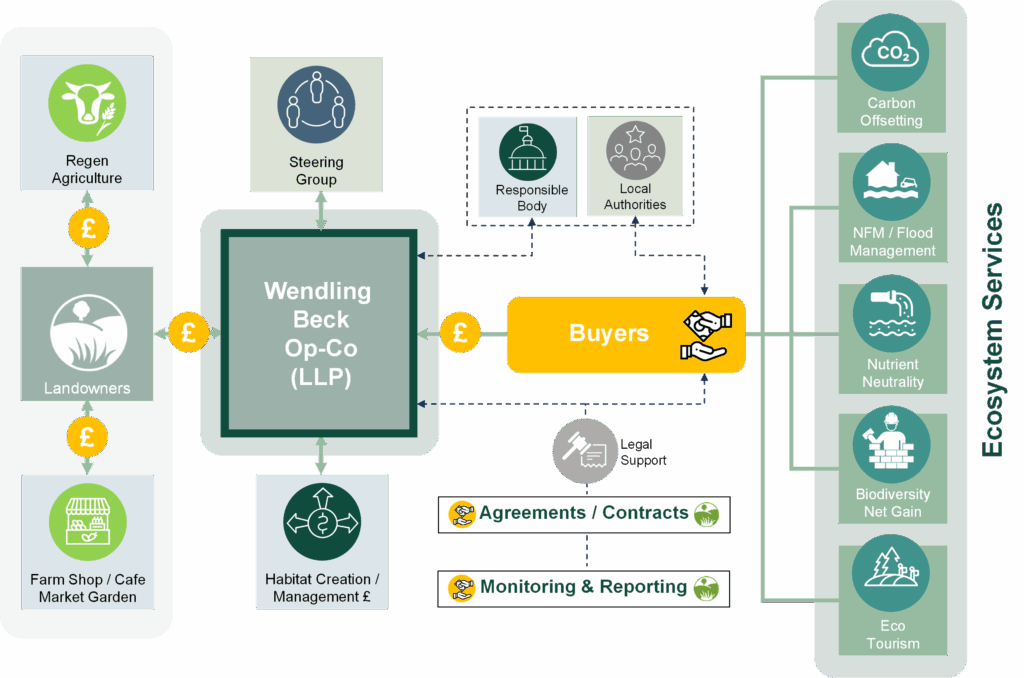

WBP is demonstrating how new compliance markets, such as biodiversity net gain (BNG) and nutrient neutrality (NN), can deliver high-integrity outcomes for nature alongside co-benefits such as natural flood management (NFM), climate mitigation, and social impact, whilst also balancing food production.

It is providing in excess of 3,000 biodiversity units, across 35 different habitat types to developers and enough nutrient credits to unlock ~2,000 homes in Norfolk. Through these and other revenue streams, employment across the Project is predicted to increase by 1,000% from the previous farming businesses.

Quick Stats

- Location: Norfolk

- Size of Land: ~2,000 acres

- Landholding sizes: 250 – 650 acres

- Tenancy & Ownership: Owner-occupiers

- Nature Market Focus: Biodiversity Net Gain, Nutrient Neutrality

- Project partners: The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Anglian Water, Norfolk County Council, Breckland Council, Natural England, Norfolk Wildlife Trust, Norfolk Rivers Trust, Norfolk FWAG

Acknowledgments

With many thanks to the following individuals for their time and insight:

Glenn Anderson, Strategy Lead and Co-Founder, the Wendling Beck Project

Rob Cunningham, Europe Resilient Watershed Programme Director, The Nature Conservancy

Date published: 04/07/2025

Key Takeaways

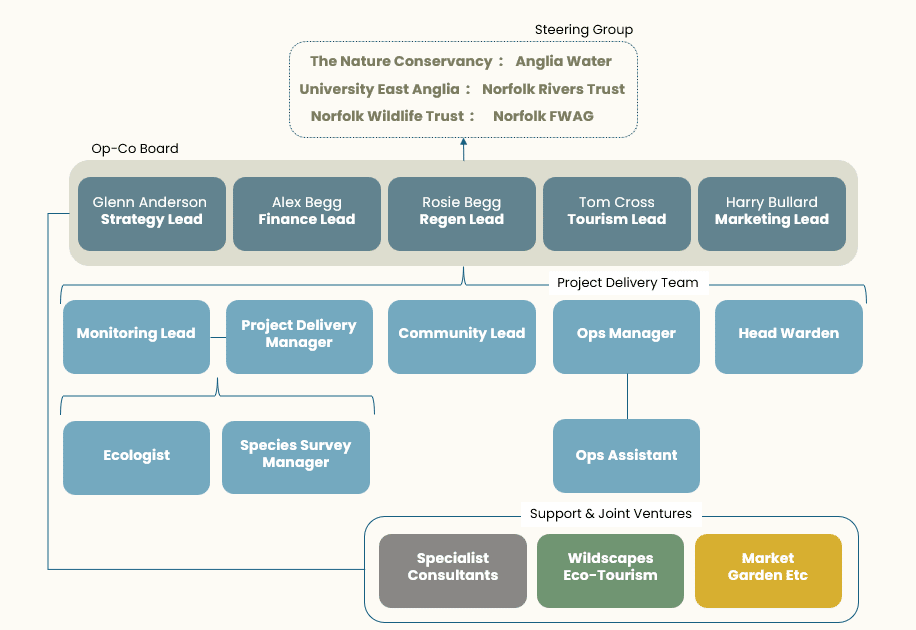

- WBP’s governance model includes a Project Board made up of the landowners, and a Steering Group of the remaining Project Partners, including eNGOs, academia and local government.

- WBP’s Habitat Management and Monitoring Plan (HMMP) drives its weekly activities and progress tracking, with habitat and ecological data is recorded regularly in WBP’s digital dashboard.

- The landowners have formed a Limited Liability Partnership (LLP) that operates as a central Op-Co for WBP, offering liabilities protection and flexibility of ownership and capital use.

- The WBP team has developed a risk management strategy, and has also offered a risk register template to other stakeholders to use in their own projects.

Decision-making and oversight

WBP is governed by a Project Board made up of the four founding landowners, who also are members of WBP’s Limited Liability Partnership – the operating company (Op-Co) entity for the Project (see below).

The Project Board meets formally twice a year, but in practice the landowners meet every week to review the progress against WBP’s HMMP (see Milestone 3) and financial model (see Milestone 5). Glenn Anderson – one of the founding landowners – says the HMMP is relied upon as a ‘bible’ to drive action and measure progress.

Each landowner holds specific responsibilities aligned with their expertise, such as regenerative agriculture and strategy (see below). Separate to the landowners, a Project Manager role was created to oversee delivery and monitoring of ecological works, working closely with the Project Board, the delivery team and managing data on WBP’s ecological dashboard (see Milestone 3).

Figure 1: WBP Team Structure

To clarify decision-making powers, WBP also created a Delegation of Authority matrix, setting out potential activities and who is required to give permission. For example, it defines the threshold at which a landowner can independently charge an unplanned expense to WBP’s central account, versus where joint approval is required from the Project Board.

Alongside the Project Board, a Steering Group provides strategic input and formalises the relationship between WBP and its main supportive partners – The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Anglian Water, Norfolk Wildlife Trust (NWT), Norfolk Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group (FWAG), Norfolk County Council, and Norfolk Rivers Trust. This advisory body was created through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) and convenes formally once a year but – as with the Project Board – maintains frequent communication and provides ad-hoc advice.

If the Project Board is in disagreement over a decision – with each of the landowners having equal voting rights – the Steering Group is permitted to step in and mediate any disputes. This a provision written into WBP’s LLP agreement, which describes a number of hypothetical scenarios (see Milestone 2).

Separate to the Project’s internal governance, WBP has also signed contracts with a Responsible Body (RSK Biocensus) for its committed BNG sites and a local council (Breckland District Council) for its nutrient neutrality sites. These organisations receive annual reports on habitat progress and any other relevant data, which is built into WBP’s overall monitoring programme.

Finally, WBP also has ongoing legal counsel from Lux Nova Partners, which leads the development and review WBP’s legal contracts (see Milestone 8).

Choosing the legal entity

Each of the landowners have their own trading entities for their landholding operations, but they wanted a central operating company for all activities that relate to WBP, including the relevant contracts, trades, assets and liabilities.

After 18 months of exploring models of single legal entities, WBP decided on a Limited Liability Partnership (LLP). Each of the landowners or their farm businesses are a member, and the LLP can enter into contracts with buyers and offtakers.

The LLP will deliver the Project, manage the habitats and enter into contracts. It will be the contact for all relevant nature market trades, and operate from a centralised project plan and governance structure.

WBP will use long-term agreements and manage the habitats over several decades – some up to 90 years. It was therefore important for the landowners to have flexibility. Advantages of the LLP include:

- Capital distributions and ownership can be determined by written agreement between the partners, including use of capital (not just retained profits) to maintain the habitats.

- New partners can be introduced more easily, for example with succession planning and sales of relevant land / farm assets.

- It enables all monies to be pooled and that central pot of money from the sale of ecosystem services can be invested to deliver a return, which will help erode inflation.

- It is easy to add on additional for-profit activities, such as eco-tourism or wildflower seed.

- The corporate structure can be set up quickly and at a low cost.

With support from BCLP, Morrison & Foerster and Lux Nova Partners, along with M+A Partners (an accounting firm), the landowners registered the Wendling Beck OpCo LLP in April 2022. Direct establishment costs were c.£150K (due to the complexity of the agreement), but it is expected to be relatively cheap to maintain each year.

Once the LLP was established, the WBP team took out Professional Indemnity, Directors and Officers, and Employers’ Liability insurance, which are all built into the ongoing administration costs of the LLP.

While scoping the right legal entity, WBP also developed a formal Environmental Social Standards policy, code of conduct, health and safety policy, and grievance procedure. These took a few months to develop with direct support from TNC.

An analysis of the other legal entities considered can be found here.

Figure 2: WBP Op-Co

Overview of Risks

WBP tracks its key risks via its risk register (template available here) that is regularly reviewed by the Project Board. Below is a list of the key risks:

- Policy risk

WBP’s chief risk comes from potential changes in government policy. Much of WBP’s income streams are dependent on nature market policy that is yet to be fully clarified, such as Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) and Nutrient Neutrality policy, along cross-cutting factors like tax treatments for landowners.

To mitigate this uncertainty, WNP signed up to several government pilots to stay connected and give feedback on how nature markets can be developed. These pilots include the Natural England BNG Pilot, the ELMs Test and Trials, and the Nature Recovery pilot, they also have representation with HMRC and HMT on the development of tax for ecosystem services. WBP is also feeding into the development of its Local Nature Recovery Strategy and has strong ties with local government.

Anderson comments: “we are definitely taking the plunge on this and are all-in, which carries a fair amount of risk. But we think that this space needs exemplars to test things, and we can use our position as a pilot to weigh in on government policy to help clarify things for other farmers. We are also benefitting from first mover advantage in the marketplace.”

- Market Risk

A significant market risk to WBP is the potential lack of market demand, for example with the c.3,000 Biodiversity Units that the WBP is looking to generate.

For this, the WBP is engaged with the Local Planning Authority for a view on market demand and is also collaborating with agents and actors representing national infrastructure projects. There is also discussions around supporting voluntary biodiversity offsets, using the BNG metric to measure outcomes. Because BNG policy generally requires developers to buy ‘like-for-like’ habitat units to compensate for their impact, the WBP believes that its range of habitats will be able to offer different BNG units to different developers, such as riverine, neutral grassland and native woodland units, which will also help to mitigate market risk.

One concern that the landowners have is that an oversupply will lead to a crash in prices. This could lead to some landowners selling at lower Biodiversity Unit prices that are not financially feasible over 30+ years. To prevent this, WBP is sharing learnings with other landowners and are being vocal about the true cost of projects over their lifetime.

- Physical Risk

WBP is creating and restoring a range of habitats – including lowland meadows and grasslands, reedbeds, woodlands and floodplain wetland mosaics, along with river restoration.

To mitigate the physical risk of habitat failure, the landowners contracted Digg & Co and eCountablity to baseline and design the new/restored habitats, both with a track record in landscape design.

WBP’s landscape masterplan has been designed to increase overall resilience. For example, the interspersed layout of the habitats will help to mitigate the threat of invasive species and plant diseases. Plant species types and the land’s hydrology, soil types and history have also been considered to account for chronic physical risks (over-nutrification) and acute physical risks (flooding and droughts). Much of the seeds used for planting habitats are sourced locally. Trees also include around 30% non-native species, which should be more climate resilient.

They have also worked closely with the Norfolk Wildlife Trust for their expertise, including on costings and contingency budgets for potential remedial works.

- Reputational Risk

Anderson notes that there was some pushback from the local community around displacing agriculture: “We assumed everyone would be behind our vision, but once we started spade-in-ground works, rumours started to take a negative spin.” In 2023, the WBP landowners wrote to local residents and held community workshops to explain the project in more detail, and it generated positive feedback and a group of local volunteers. Now, WBP has a group of semi-formal volunteers that it aims to get on-site at least three times a year, and hopes to establish a more formal partnership with the local councils to improve the educational opportunities from volunteering. Anderson would advise other projects to start with community engagement before work starts on the ground.